2025-07-06 JavaScript

Event Loop & JS runtime

I wasn't really active recently due to the increase in work and university load, but I came back with one of the core concepts of JavaScript, its runtime and how it works, a simple yet powerful mechanism that allows JS to work asynchronously despite having only one thread of execution.

JavaScript runtime is made up of:

- JS Engine (Heap and Call Stack)

- Web APIs

- Microtask Queue

- Macro Task Queue (or Task Queue, any of these names are correct and used interchangeably)

- Event Loop 🔁

In the JS engine, in this article, I will talk only about the Call Stack queue. That is what I consider the main thread of execution. Any function that the program runs should enter the Call Stack queue and get removed from it once it's executed. But if a task is time-consuming, such as a network request for data fetching or heavy computation, it can block the main thread of execution for a relatively long time until its computation is over.

This is the synchronous method, where the rest of the code must wait for the result of the earlier code execution. But in asynchronous code, you can have a signal indicating to start the execution elsewhere, kind of parallel, and once you have the results, then execute the code via the main thread and remove it afterward. This is exactly how JS works behind the scenes.

Nowadays, web browsers are state of the art standalone products, and they do way more than just rendering the content from the internet. One of the key capabilities of modern web browsers is their APIs, such as fetch, localStorage, sessionStorage, XMLHttpRequest, setTimeout, and document. At the interface of these APIs, these API calls must happen in an asynchronous manner to avoid blocking any other code in the thread.

The browser API has two return methods, either by a callback function or via a promise.

Any time the Call Stack notices browser API-related code, it sends it directly to the Web API section of its runtime to allow further processing there.

On the Web API side, once the browser-specific operation is done, such as a network request or setting the timeout, the result will be returned into two separate queues. If they return via a callback function, they will go to the Macro Task Queue. If they return a promise, they will be sent to the Microtask Queue.

The Event Loop’s job is to check on each iteration to see if the main Call Stack is empty. If it is, it first lets the code from the Microtask Queue run. Once it’s empty and there’s nothing else in the Call Stack, it proceeds to run all the Macro Task Queue items 🔄.

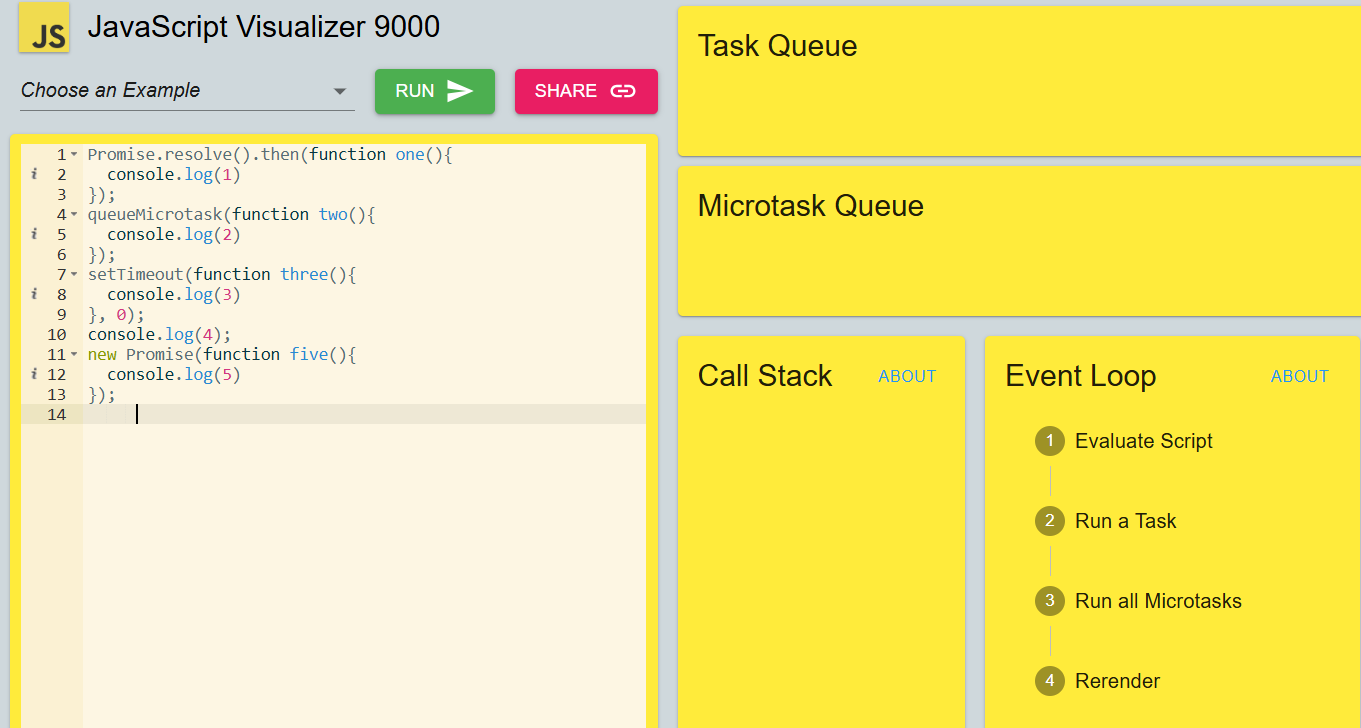

Practice time To get a better understanding of this whole concept, I have prepared an example that you can try:

jsPromise.resolve().then(function one(){

console.log(1);

});

queueMicrotask(function two(){

console.log(2);

});

setTimeout(function three(){

console.log(3);

}, 0);

console.log(4);

new Promise(function five(){

console.log(5);

});

In the code above, which console.log() gets printed first? And try to think about which queue, if any, each part belongs to.

If you want to visualize it, head to 👉👉👉https://www.jsv9000.app/ 👈👈👈 and use the code there to get a visual representation of the runtime's behavior in action.